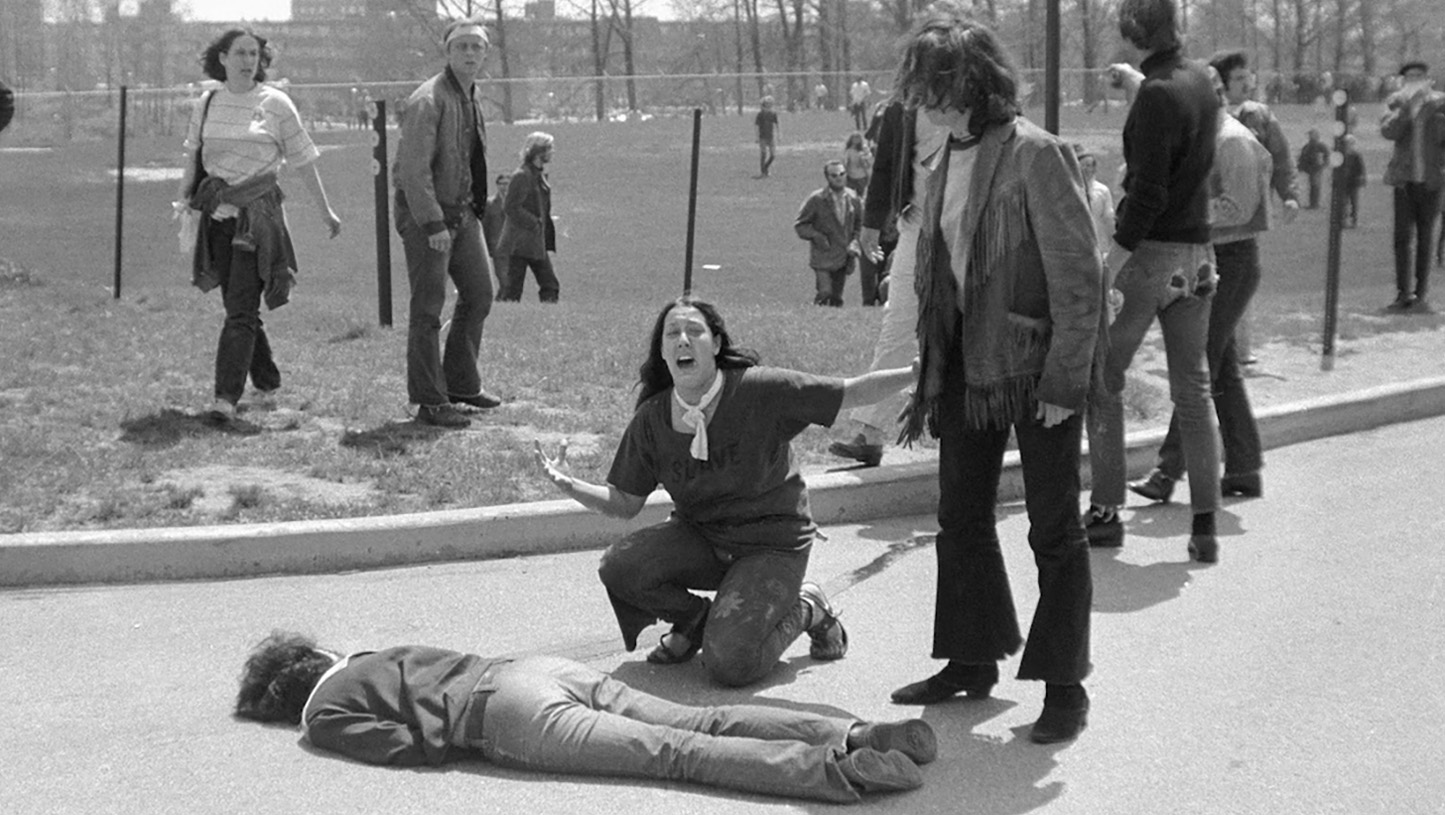

The cost of dissent. Photograph by John Filo, Kent State University, May 4, 1970. Pulitzer Prize-winning image depicting Mary Ann Vecchio grieving over Jeffrey Miller. Four days later, Neil Young penned Ohio after seeing this image, transforming the National Guard shootings from “crowd control” into political assassination through song. Photo source: Appleton Post-Crescent (Dec. 5, 1976); image believed to be in the public domain in the U.S.

The Arts Help Us Decide

Assassination is never “just” a killing. A single body falls, but the political shockwaves reach across societies, generations, even continents.

The line between murder and political assassination isn’t always clear. Was it treachery or patriotism? Martyrdom or propaganda?

One way we sort these questions is through the arts.

Theatre, painting, photography, illustration and street art do more than document violence. They frame it. They push us to mourn, to rage, to act. Or, to forget.

Sometimes they function as ephemeral propaganda, serving an immediate political agenda. Sometimes they become enduring art, reshaping how generations understand history.

Often, they are both.

Here are works across time and media that reveal how the arts helps us decide what political assassination means.

“Hail, Caesar”—or Heil? Actors in the Mercury Theatre’s 1937 production of Julius Caesar extend the Nazi salute in a chilling nod to rising fascism. Orson Welles’s adaptation recast Shakespeare’s Rome as a modern dictatorship, blurring the line between ancient ambition and contemporary tyranny. Photographer unknown. Image believed to be in the public domain.

Betrayal or Patriotism?

Shakespeare, Julius Caesar (1599)

Brutus and the conspirators strike Caesar down not as common murderers, but as self-proclaimed saviors of the Republic.

Shakespeare refuses to answer whether they were right. Caesar is ambitious, but is his ambition tyranny? Brutus is honorable, but is he also naïve?

Because the play refuses to settle the question, it avoids propaganda and endures as art. Every generation restages it to ask: when does violence against power become political necessity?

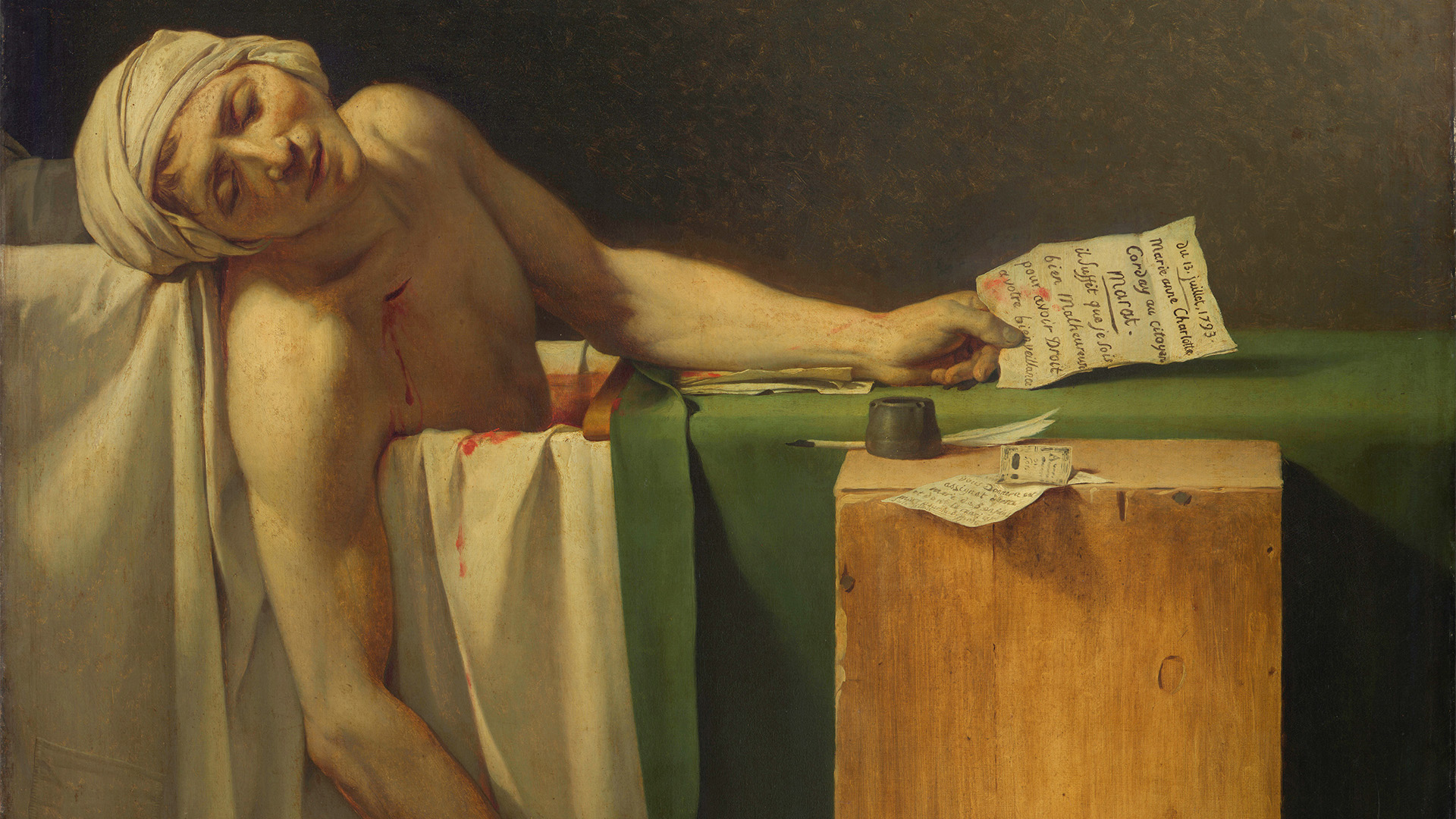

Martyrdom in oil and silence. Jacques-Louis David’s The Death of Marat (1793) immortalizes the slain revolutionary journalist Jean-Paul Marat, stabbed in his bath by Charlotte Corday. Rendered with stark restraint, the painting transforms political violence into sacred lament, an icon of radical sacrifice. Image Credit: Jacques-Louis David, The Death of Marat (1793). Oil on canvas. Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Martyrdom as Propaganda

Jacques-Louis David, The Death of Marat (1793)

When Charlotte Corday stabbed Jean-Paul Marat in his bath, he died bloodied and half-naked. But David’s canvas transforms him: the radical journalist lies serene, pen in hand, glowing with saintly calm. The assassin is absent.

Painted just months after the killing, the work was pure revolutionary propaganda. Marat became a martyr, his murder a rallying cry. Yet the painting’s haunting composition and emotional power gave it a second life.

Today it is studied as one of Western art’s masterpieces, an example of propaganda aging into art.

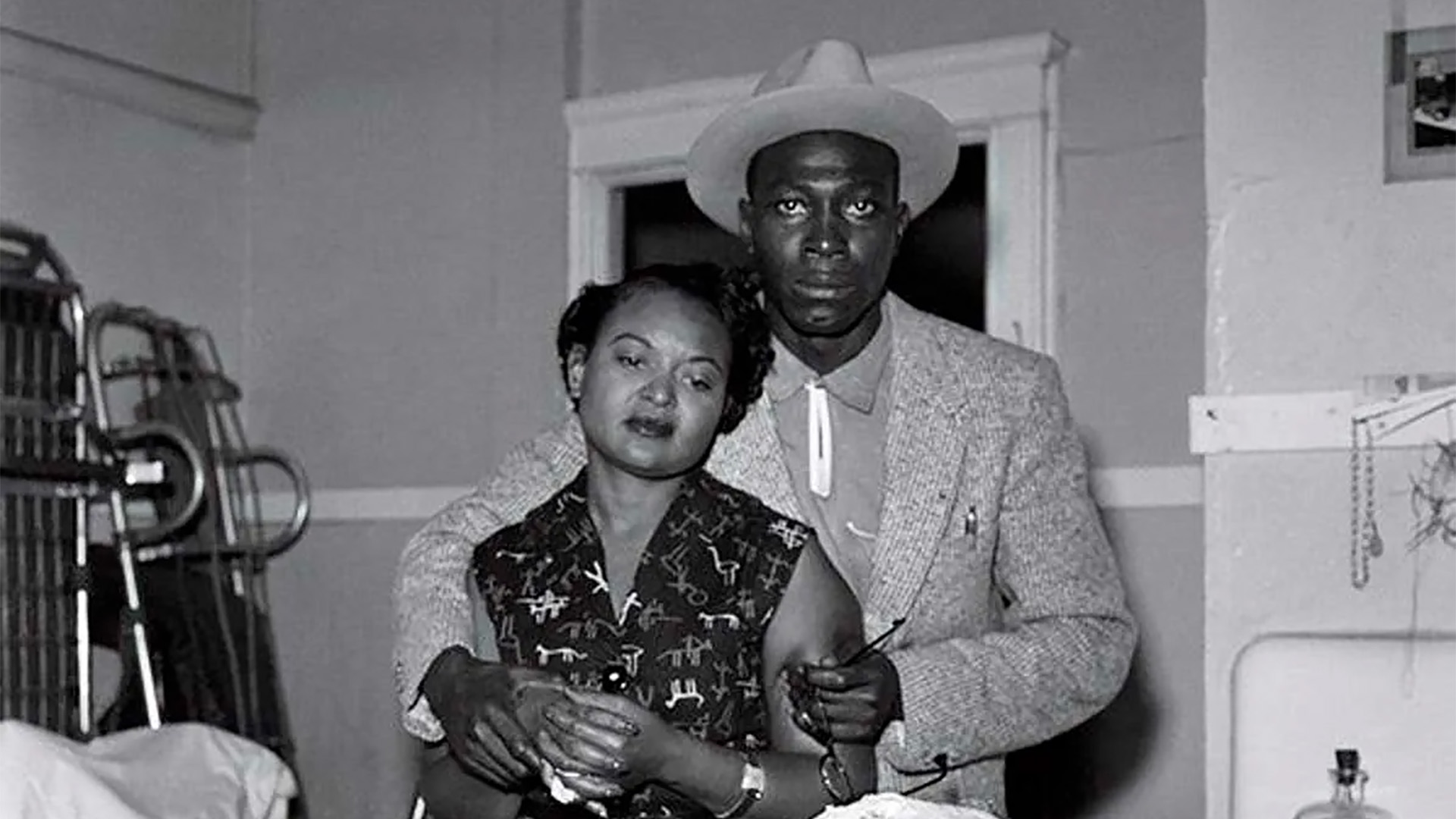

The gaze that endures. Mamie Till is held by her future husband, Gene Mobley, as she views the body of her son, Emmett Till, aged 14. She insisted on an open casket so that the world “could see what they did to my baby.” That act of courage galvanized a movement and exposed the brutality of American racism. Image source: Meridian Star. Photographer: David Jackson.

Terror Made Visible

Photographs of Emmett Till’s open casket (1955)

When 14-year-old Emmett Till was lynched in Mississippi, his mother insisted on an open-casket funeral. Jet magazine published the photographs: Till’s brutalized face, visible to the world.

These were not stylized works of art. They were documentary images meant to shock, and they worked like propaganda, mobilizing outrage and fueling the civil rights movement. Yet their endurance lies in their truth. They cannot be aestheticized away.

They remain some of the most powerful images of racial violence in America.

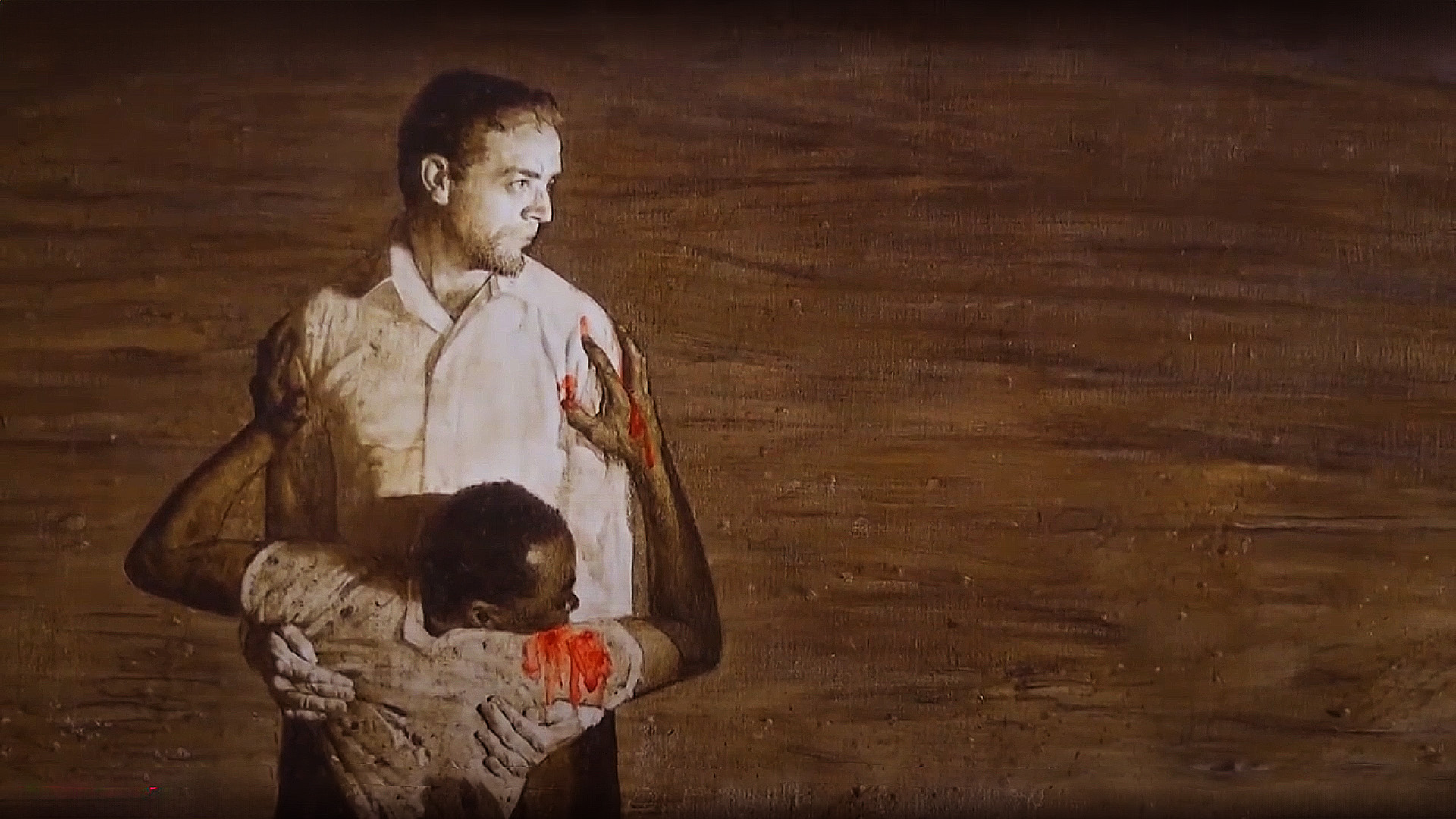

Southern justice, unfinished. Norman Rockwell’s 1965 painting Murder in Mississippi depicts the final moments of civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner. Commissioned for Look magazine, the image echoes Goya’s Third of May and stands as one of Rockwell’s most politically charged works. Detail of oil on canvas painting sourced from YouTube video about the piece by Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge, MA.

Democratic Fragility

Norman Rockwell, Murder in Mississippi (1965)

Through his depictions of Thanksgiving dinners and smiling families, Rockwell was famous for wholesome Americana. But in the 1960s he shifted to social justice.

His painting Murder in Mississippi depicts the bodies of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, civil rights workers murdered for registering Black voters.

Commissioned for Look magazine, the work lived in the churn of the news cycle. Yet its stark portrayal of young men felled by hate has endured as more than illustration. It marks a turning point: even America’s most “apolitical” painter had to face political assassination.

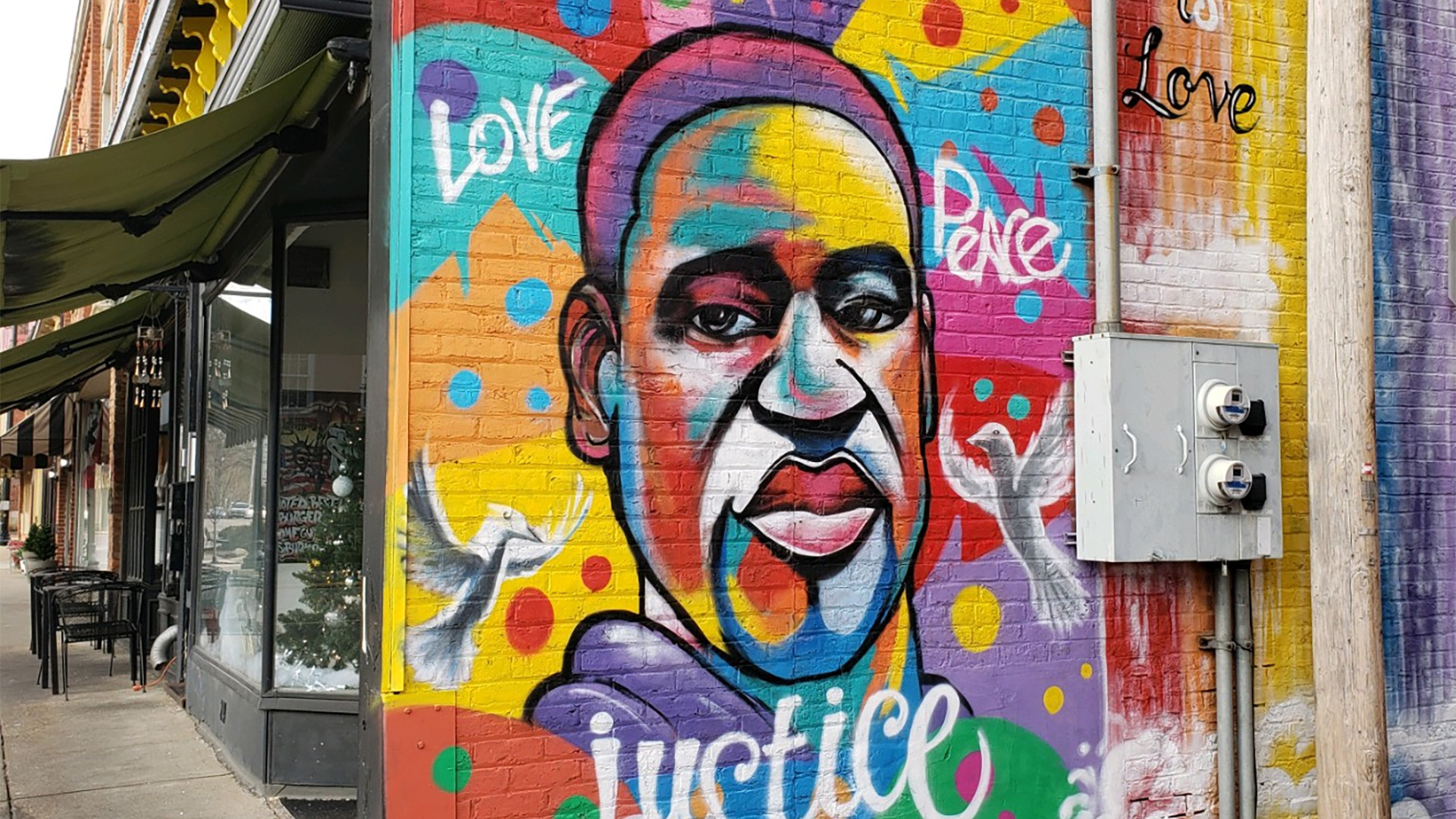

Love, peace, unity—and protest. A mural honoring George Floyd rises in Marietta, Ohio, painted in August 2021. Though intended as a tribute, the artwork sparked local controversy, revealing the fault lines beneath public memory and racial reckoning. Mural by Robert Durst. Photograph by Robin Shaw. Published by Urban Art Mapping. Image ID: UAM-GF_3121.

Global Iconography of Resistance

George Floyd murals (2020)

After George Floyd was murdered by police in Minneapolis, his image appeared overnight on walls and sidewalks across the world. In Nairobi, Berlin, Belfast, and beyond, artists rendered his face with the word: Justice.

Street art is often ephemeral, painted over, washed away, erased. But Floyd’s image multiplied, archived in photographs, replicated endlessly online.

What began as protest graffiti became a global emblem of resistance. Ephemeral memorials turned into enduring art through sheer collective repetition.

Conclusion: Propaganda or Art? Both.

Assassinations and their artistic depictions live on two timelines:

- On one, there is the immediate political need: to sanctify, vilify, mobilize or suppress.

- On the other, there is the longer arc of art: works that outlive their moment, continuing to trouble and inspire.

Julius Caesar keeps asking whether assassination can ever be noble. David’s Marat shows how propaganda can become beauty. Emmett Till’s photographs reveal how documentary shock can be more enduring than a painting.

Rockwell’s Murder in Mississippi shows art shifting under political pressure. And Floyd’s murals remind us how even temporary marks on a wall can reshape global consciousness.

So, what is political assassination?

Art doesn’t settle the question. It keeps it alive, forcing each generation to decide whether a killing is private violence, or a wound to the body politic.

Randall White

Abbetuck

Photographs above are reproduced under the principles of fair use for purposes of historical analysis, public commentary and educational reflection. They are central to this Substack post’s critique of state violence, the role of photojournalism in shaping collective memory and the ethics of visual protest. No commercial gain is derived from their use, and attribution (where known) is provided to honor the photographer’s legacy and the image’s cultural significance.

No responses yet