Detail from John Singer Sargent’s 1889 portrait of Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth. (Public domain / Wikimedia Commons)

The Perfect Crime Against Accountability

What if I told you there’s a rhetorical device so powerful it can flip guilt into innocence, aggressors into victims, and calculation into nobility, all while preserving deniability?

Artists across centuries have been fascinated by this psychological sleight of hand: strategic martyrdom.

Unlike true martyrdom, this is victimhood as performance, suffering as currency, and moral authority as weapon.

The pattern is seductive in its simplicity:

- position yourself as the wounded party,

- claim the moral high ground, and

- deflect any examination of your own role in creating the chaos around you.

The cast of Arthur Miller’s The Crucible at Central Square Theater, Cambridge. (Photo: Nile Scott Studios / Central Square Theater)

Masters of Self-Deception

Tennessee Williams understood this psychology intimately. In The Glass Menagerie, Amanda Wingfield’s constant refrain of being a “Christian martyr” isn’t about real sacrifice, it’s about avoiding accountability for her suffocating control over Laura and Tom.

By casting herself as the long-suffering mother, she deflects examination of how her own unrealistic expectations and manipulative behavior contribute to her children’s misery.

Why Williams deployed this technique: To reveal how people construct elaborate narratives to avoid confronting their own complicity in their disappointments. Amanda’s martyrdom rhetoric protects her from the painful truth that she’s partly responsible for her family’s dysfunction.

Arthur Miller’s John Proctor in The Crucible presents a more complex case. His final martyrdom serves dual purposes: genuine principle and reputation rehabilitation. Proctor needs to see himself as a martyr to live with his past adultery and cowardice.

Why Miller used this: To explore how self-interest can distort even “noble” acts, and how the line between heartfelt sacrifice and psychological self-protection often blurs.

Calista Flockhart and Zachary Quinto in Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? at Geffen Playhouse. (Photo: Jeff Lorch / Geffen Playhouse)

Weaponizing Wounded Pride

Edward Albee dissected this psychology ruthlessly in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Martha repeatedly positions herself as martyred by George’s professional failures and sexual inadequacy. This victimhood narrative gives her license to be increasingly cruel while avoiding examination of her own destructive behavior.

Why Albee employed this: To expose how couples use victimhood as ammunition, turning genuine grievances into weapons that justify escalating cruelty while maintaining moral superiority.

Martha plays the victim card the same way politicians do today, turning hurt feelings into justification for going on the attack.

Shakespeare’s Lady Macbeth offers a masterclass in strategic suffering. Her sleepwalking scene (“Here’s the smell of the blood still”) transforms her from calculating manipulator into tortured victim of her own conscience.

Why Shakespeare used this device: To show how individuals may perform guilt without truly feeling it, and how even an authentic psychological breakdown can serve self-exonerating purposes.

Joan Crawford in a publicity still for Mildred Pierce (1945). (Public domain / Artbook)

The Camera Never Lies (Except When It Does)

Joan Crawford’s Mildred Pierce embodies this pattern perfectly. She constantly frames her sacrifices for her ungrateful daughter Veda as noble martyrdom, but this self-presentation masks her need for control and validation. Her “suffering” becomes moral currency that excuses her enabling of Veda’s increasingly destructive behavior.

Why this resonated: Post-war audiences were grappling with changing gender roles. Mildred’s strategic martyrdom offered a way to maintain traditional notions of maternal nobility while critiquing the psychological costs of that performance.

Film noir protagonists routinely employ this device. They frame themselves as corrupted by circumstances beyond their control, when really they’re making deliberate choices driven by greed, lust or ambition.

Mildred acts like she’s some kind of martyr, which reminds me of how people nowadays dress up their power moves as sacrifices, making themselves look noble when they’re really just grabbing control.

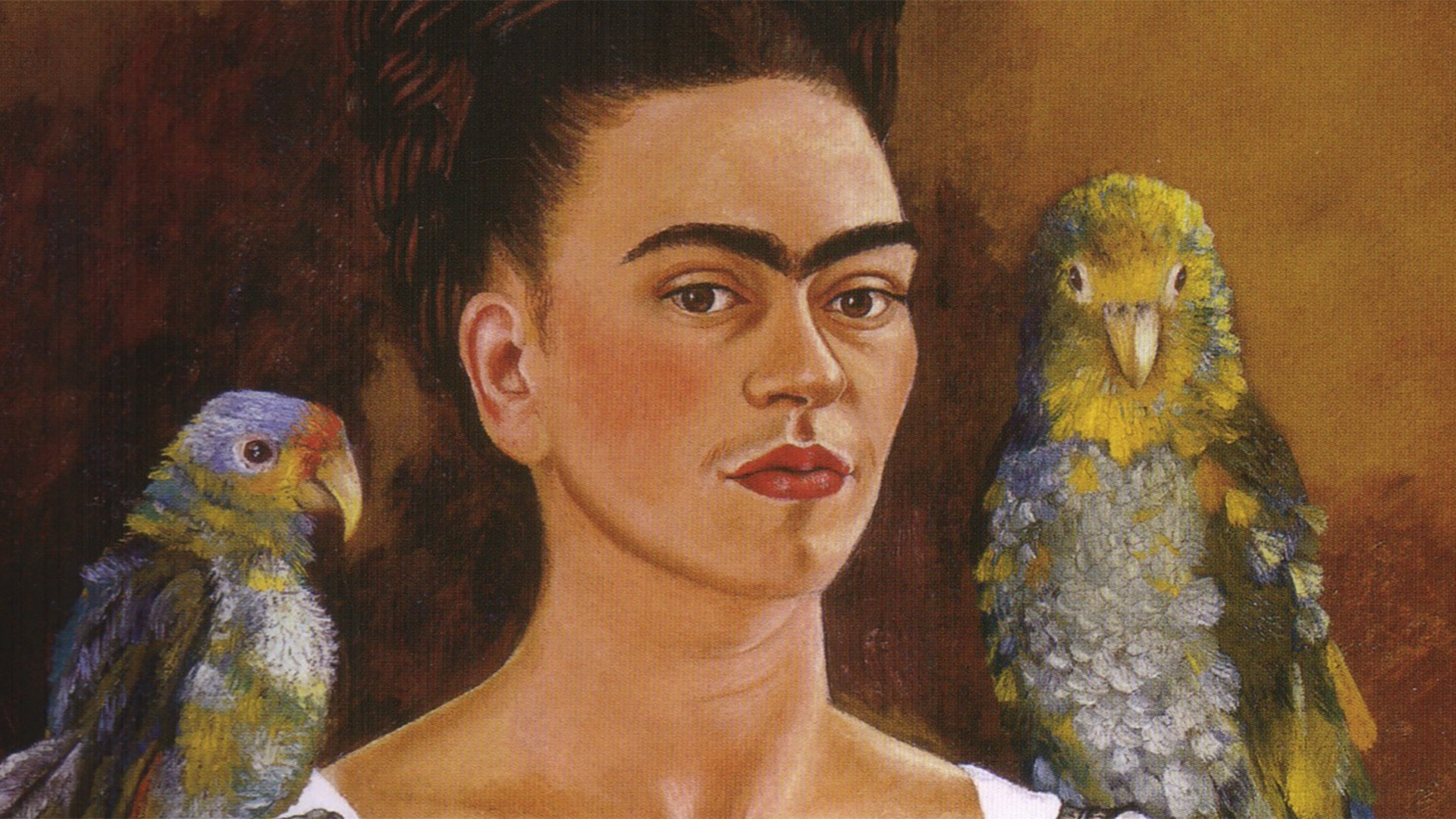

Frida Kahlo’s Me and My Parrots (1941), oil on canvas. (Public domain / Harold H. Stream Collection, New Orleans)

Painting Pain as Power

Frida Kahlo’s self-portraits bristle with martyrdom iconography (thorns, wounds, religious imagery) but was this earnest suffering or calculated self-mythologizing? Kahlo transformed personal pain into artistic currency and political credibility.

Why this mattered: In a male-dominated art world, pain was power. While male artists could rely on bravado, Kahlo weaponized vulnerability

The Psychology Behind the Performance

Why are artists so drawn to this pattern? Because it reveals something fundamental about human psychology:

- The Moral Laundering Effect: Martyrdom rhetoric transforms agency into victimhood, calculation into noble suffering. It’s psychologically seductive because it allows people to maintain their self-image as “good” while doing harmful things.

- The Authority Grab: Suffering confers moral authority in most cultures. By positioning themselves as victims, characters (and people) claim the right to judge, punish and demand without reciprocal accountability.

- The Deflection Shield: Nothing shuts down criticism like victimhood. Once you’re established as the wounded party, examining your own contributions to the situation becomes tantamount to “victim blaming.”

Why Artists (of All Disciplines) Keep Returning to this Well

Artists employ this device because it’s simultaneously:

- Recognizable: We’ve all encountered people who weaponize their suffering.

- Uncomfortable: It forces us to examine our own capacity for self-deception.

- Dramatically rich: The tension between performed and genuine suffering creates complex, layered characters.

- Socially relevant: In an age of competing victimhood narratives, understanding strategic martyrdom is more crucial than ever.

Johnny Cash in the official music video for his cover of Nine Inch Nails’ Hurt. (Screenshot from official video / UMe / American Recordings)

The Ultimate Artistic Insight

The most sophisticated artists understand that the line between sincere suffering and performed victimhood often blurs.

By positioning himself as the wounded, repentant sinner reflecting on his mistakes, Johnny Cash’s cover of Hurt transforms his history of drug abuse, infidelity and destructive behavior into a narrative of noble suffering and hard-won wisdom.

This is what makes the martyrdom ploy so psychologically complex and artistically fertile: it’s rarely pure manipulation. It’s usually a mixture of real pain and strategic positioning, authentic grievance and calculated victimhood.

The best artists don’t excuse their martyrs, they illuminate the seductive psychology that makes strategic victimhood both powerful and perilous.

Sound familiar? It should.

We’re living through a masterclass in it right now.

Randall White

Abbetuck

No responses yet