Stolpersteine (stumbling stones) are small brass plaques embedded in walkways across Europe, each commemorating a victim of Nazi persecution. They don’t tell you to mourn. They let you stumble into memory, literally and figuratively (Thomas Kienzle/AFP)

How Artists Carry Resistance in Silence and Symbol

Not every truth can be spoken. But artists have always found a way to convey it. Through shape, silence, metaphor and repetition, they carry what must survive — even when it can’t be said aloud.

This isn’t about hiding. It’s about protecting what matters. It’s about building shared languages when the spoken one betrays you.

“No Exit” by Jean-Paul Sartre, as staged in 2006 by the American Repertory Theater at Harvard University (back when Harvard had courage).

Codes Between Creatives

How do artists tell the truth when language fails?

- Through symbols buried in myth and nature. A feather that always falls toward the east.

- Through formal structure. A play where the story happens between acts.

- Through pattern and repetition. A beat that mimics the march of the unnamed.

- Through layered meaning. A photograph that frames the absence rather than the subject.

These codes aren’t decoration. They’re armor. Artists use them to carry resistance through time, space and censorship.

In times of great scrutiny or repression, artists may embed truth where it can’t be intercepted — not by hiding it, but by layering it so that only those prepared to receive it will know it’s there.

Jean-Paul Sartre’s “No Exit,” written during the Nazi occupation of France, does just that. At first glance, it’s a dark room with three bickering souls. But look closer: it’s a smuggled message about moral responsibility in a time of moral collapse.

Sartre couldn’t name the fascists. He didn’t have to. His audience (if they listened) already knew.

“Obey Giant” mural (2015) created by artist Shepard Fairey in Detroit, MI.

What We Learn When We Decode

Interpretation isn’t a luxury. It’s survival.

When truth is in disguise, the role of the audience changes. We become interpreters. Carriers. Witnesses. To notice is to resist. To understand is to carry forward. To feel, fully and despite silence, is to keep something alive.

What can you understand when you’re willing to look twice, read twice, hear twice? When truth is dangerous (or simply ignored) artists sometimes disguise it.

Shepard Fairey’s “Obey Giant” campaign did this not by hiding the message, but by making it so opaque, so absurd, that it slipped past cultural gatekeepers.

It looked like propaganda. It mimicked authority. It blended into the visual noise of power. And in doing so, it mocked the very idea of blind obedience.

But the work doesn’t tell you what to think. It doesn’t rescue you with clarity. It simply dares you to ask, “Why am I obeying?”

The moment you do, the disguise falls … and you’ve already changed.

Toni Morrison’s “Beloved” (1987) won the 1988 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and was a finalist for the 1987 National Book Award.

Artists as Architects of Memory

Even under repression, artists don’t just protest, they build frameworks for remembering. Their hidden truths become cultural memories, carried in:

- Choreography

- Typography

- Symbolism

- Spiritual resonance

The work doesn’t shout. It reverberates across generations.

Toni Morrison’s “Beloved” does not announce itself as protest literature. It doesn’t campaign. It doesn’t argue. Instead, it haunts, it fractures, it demands that you sit inside a silence that holds too many names.

Through metaphor, ghost, and broken memory, we carry what hurt too much to name, what defied safety, what the world tried to forget.

“Beloved” does not scream. It echoes. And in that echo, it keeps alive the truth that so many systems tried to erase.

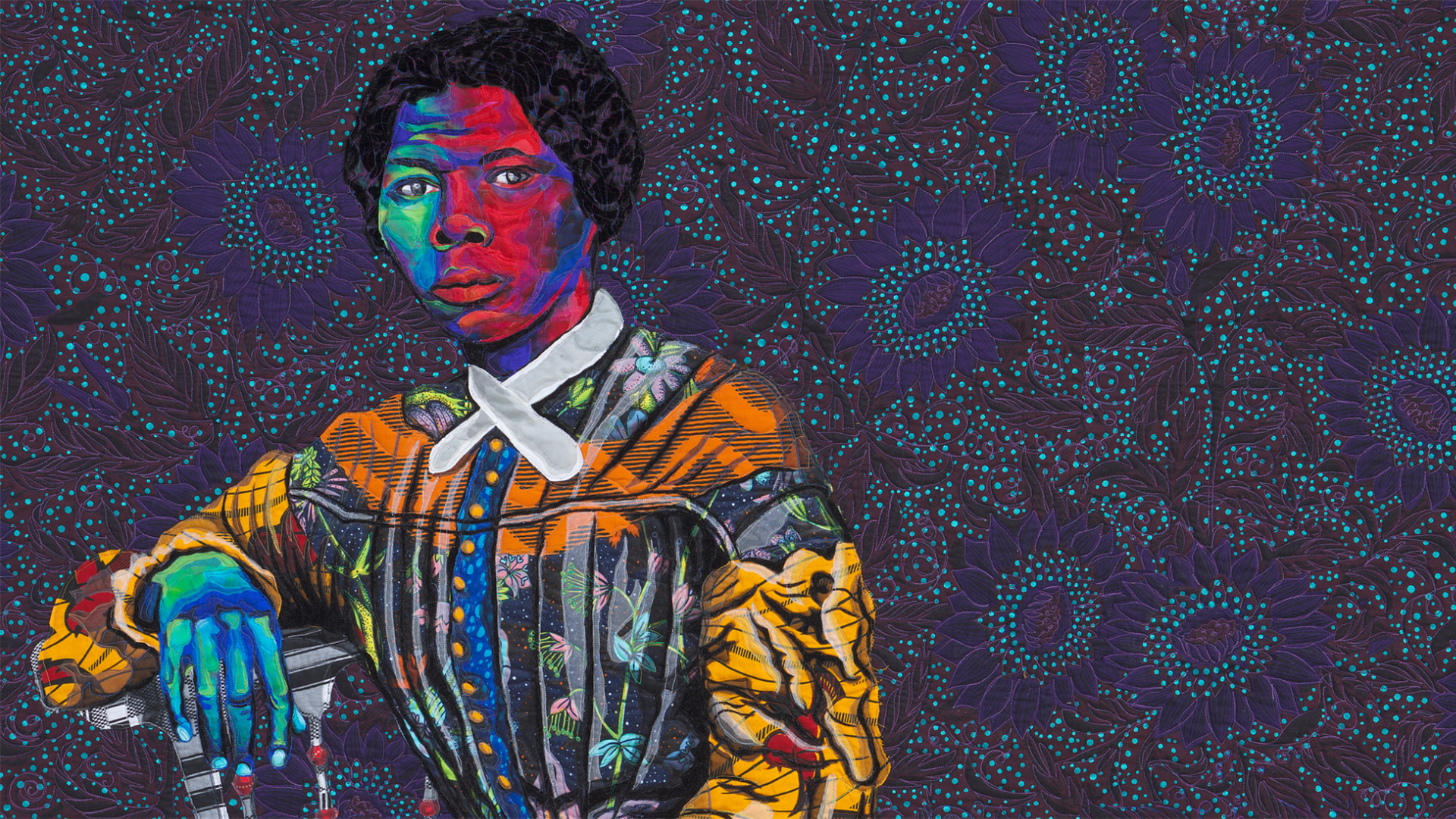

Bisa Butler’s quilted and appliquéd textile portrait of Harriet Tubman, “I Go to Prepare a Place for You” (2021), is in the collection of the National Museum of African American History and Culture. It is a visual memory and a legacy written in code.

When Artists Hide Truth, It’s Never to Bury It

So, I end on this note. Not with answers or directives, but with a call to sense more deeply.

Whether you create or observe, decode or remember: Listen longer. Look closer. Let what’s unspoken stir something unshakable. Let metaphor ache. Let silence hold shape.

What will you do with the truth you’ve encountered? In your own discipline, leave a trace. Code something quietly defiant. Design something that resists forgetting.

Or, simply be the keeper of memory. An accomplice to truth. A witness with eyes open.

Randall White

Abbetuck

No responses yet