The mill owners called it “helping out.” Lewis Hine’s lens called it what it was: child labor. When polite language hid exploitation, a photograph broke the code.

The Coded Violence Around Us

Look carefully.

- A peaceful protest turns into “a threat to public order.”

- Officials explain a neighborhood raid as “protecting national security.”

- Armed agents with no warrant arrest a citizen but the press calls it “preventive detention.”

- A black van pulls up at night and a person simply vanishes. The official story says, “Move along. Nothing to see here.”

This is what coded violence looks like.

Coded violence means harm disguised by polite language, official lies or propaganda that hides what’s really happening.

When political power wants to control through fear, it rarely admits to what it is doing.

Secret police don’t advertise themselves as kidnappers. They call themselves guardians of stability. Paramilitary gangs aren’t just thugs, they’re “enforcement officers,” “mission support personnel” or “patriots.”

The violence is real, but the words used to explain it are murky.

Euphemisms, denials, spin…

If we accept the story, we pretend nothing’s wrong. If we question it, we become the next target.

However, people have always found ways to see through this fog.

Artists, musicians and writers give us the tools to decode the code.

- A photograph that shows the masked faces behind the official lie.

- A song that hides a protest inside a lullaby.

- A poem that slips forbidden truth past the guards at the border.

Throughout history, the arts have offered something precious: a way to say, “Look closer. You are not imagining this.“

When a truth is too dangerous to state openly—because doing so could get you censored, jailed or killed—the arts can wrap that truth in forms that make it survivable.

The truth is still there. It is either disguised, coded, or softened enough to slip past censors and secret police or it lives on in people’s minds when it can’t live in public speech.

This is not just history. It’s taking place right now. Every morning when you review the latest news of political lies and chaotic tyranny, consider how the arts can both decode the lies and flaunt the truth.

Neither is this theory. Across time and place, artists have found ways to speak the unspeakable.

Examples of How the Arts have Decoded Violence

Spirituals That Led the Way

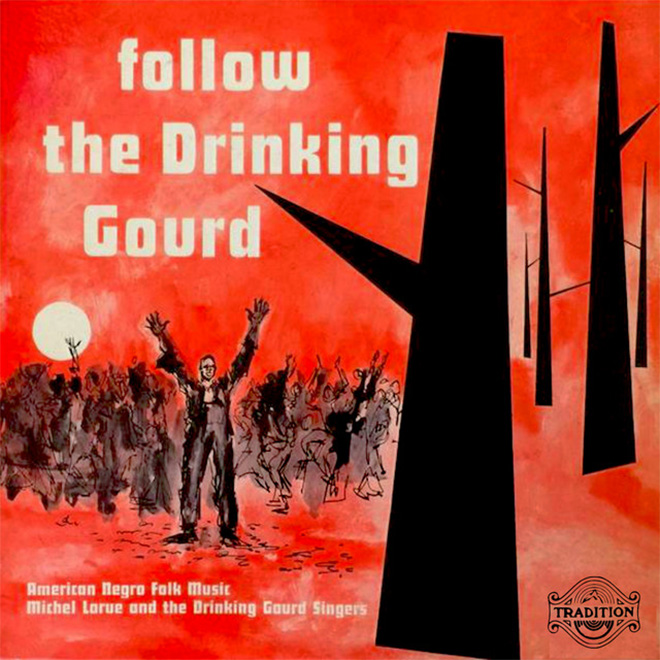

Songs like “Follow the Drinking Gourd” sounded like simple spirituals. But they hid instructions for the Underground Railroad. The song was the hiding place for a forbidden truth: how to escape. There was no pamphlet for runaways to follow. The song “carried” the map.

Image: Michel LaRue, Alex Foster and The Drinking Gourds released the album “Follow the Drinking Gourd” in 1954.

Poetry That Hid In People’s Heads

In Stalin’s USSR, people waited for years outside prisons for news of “disappeared” loved ones. The government did not allow people to talk about this. Officially, the disappearances weren’t happening.

Anna Akhmatova‘s poem “Requiem” told that exact truth … the knock on the door, the line outside the prison, the fear of betrayal … but did so in tight, symbolic, lyrical lines. She didn’t publish it. People memorized it. The poem hid the real story, where the regime couldn’t seize it.

Image: 1922 portrait of Anna Akhmatova by Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin.

Visuals That Packed a Punch

Ai Weiwei’s installation, “Remembering,” used 9,000 children’s backpacks on a museum facade to spell out a phrase from a mother whose child perished in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake.

Thousands of children died because of corruption and censorship and the government had covered up shoddy school construction. The backpacks spelled: “She lived happily on this earth for seven years.”

Image: Ai Weiwei’s “Remembering” (2009). Haus der Kunst, Munich.

Where We Go Next

In the weeks ahead, I’ll be sharing more stories of how the arts confront state terror. I hope you’ll join me and bring others with you.

Because when the truth is under threat, the arts keep it alive.

Randall White

Abbetuck

No responses yet