Langston Hughes, photographed in Kodachrome by Carl Van Vechten, 1936. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Library. Public domain.

The Poet Who Wrote in Blues and Called It Literature

Pressure From Every Direction

In the 1920s, Langston Hughes faced pressure from every direction. White publishers wanted him to write “universal” poetry that downplayed his Black identity. Some Black intellectuals wanted him to write only “respectable” literature that would uplift the race’s image. Everyone wanted him to translate his voice into something more palatable.

Hughes refused.

The Choice That Changed Literature

Instead, he wrote poetry in the language and rhythms of everyday Black folks. He incorporated blues, jazz, and street vernacular into literature. His poem “The Weary Blues” brought the actual sound of jazz onto the page. Critics called it “low” and “undignified.”

Hughes didn’t care. “We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame,” he wrote. He could have had an easier career writing safe, acceptable verse. Instead, he chose to preserve and celebrate the full spectrum of Black expression.

That choice helped birth the Harlem Renaissance and gave permission for generations of writers to use their authentic voices rather than code-switching for literary acceptance.

Why Authentic Voices Matter

Here’s why Hughes’ creative courage matters beyond poetry: When artists refuse to sanitize their experience, they expand what’s possible for everyone. They prove that authentic expression resonates more powerfully than polished respectability.

Hughes trusted that his truth was universal enough to speak to others, even when expressed in his own specific voice. He was right. His poetry didn’t just reach Black readers or jazz lovers. It reached anyone who recognized the human experience underneath the cultural specifics.

This is how creative freedom drives cultural evolution. One artist’s refusal to compromise their voice creates space for others to be authentic too.

Hughes didn’t just write great poetry. He demonstrated that literature could sound like real people talking, feeling, and living.

Every writer who refuses to translate their experience into “proper” English, every artist who draws from their community’s traditions instead of approved forms, every creator who trusts their authentic voice over market expectations is walking the path Hughes cleared.

Cultural vitality depends on artists like Hughes having the courage to say: This is how my world sounds. This is how my people talk. This is how we make meaning. And this belongs in art just as much as anything else.

Randall White

Abbetuck

Read the complete Creative Freedom series:

- When Jazz Found Its Voice in a Funky Dance Hall

- The Revolutionary Who Painted Himself Back into a Corner

- The Woman Who Painted Flowers Like Monuments

- One Small Act of Creative Courage You Can Take Today

Langston Hughes

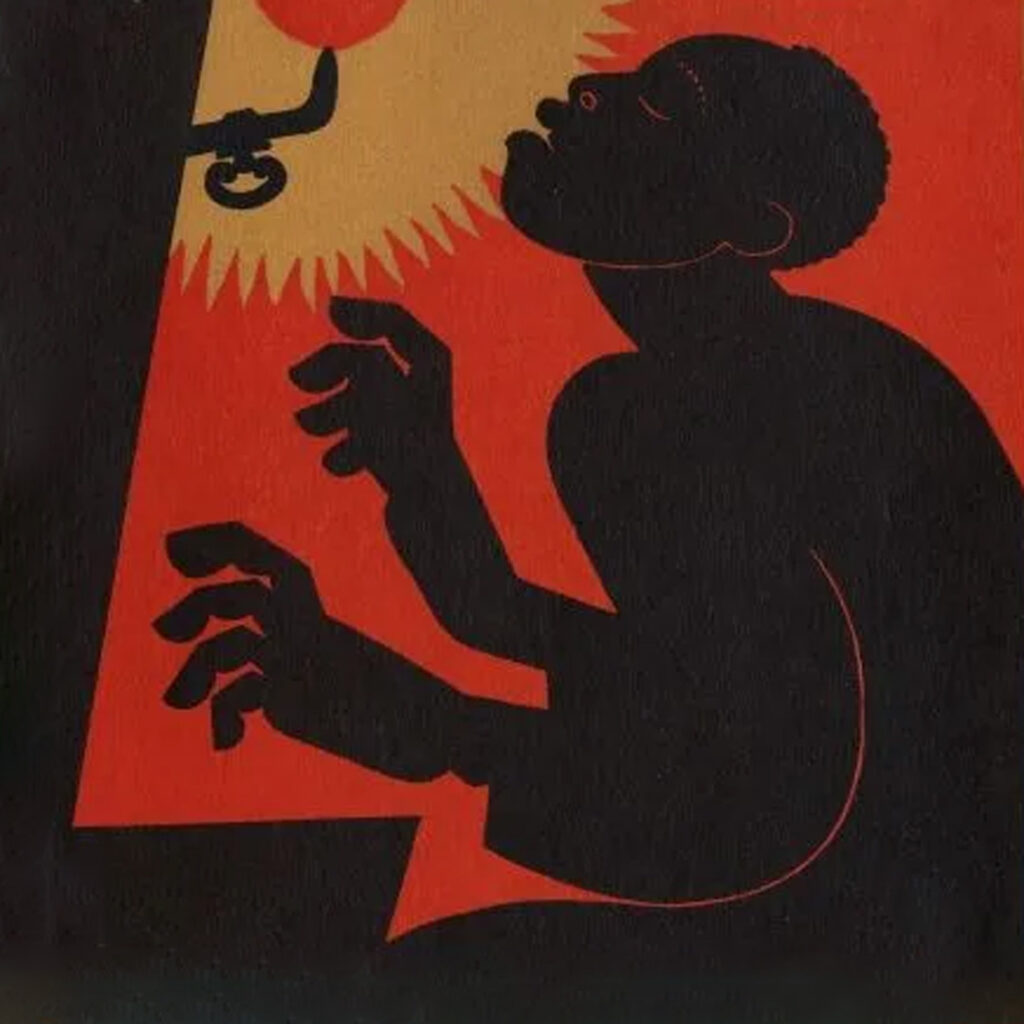

The Weary Blues, 1926. Poetry collection capturing the rhythms and experiences of African American life. Graphic shown adapted from paper dust jacket design by Miguel Covarrubias. Courtesy of National Museum of African American History and Culture.

No responses yet